AP Syllabus focus:

‘Innovations in technology, agriculture, and commerce accelerated the economy, reshaping U.S. society, work, and regional identities in the early 19th century.’

The market revolution transformed the United States between 1800 and 1848, integrating regions, boosting productivity, and reshaping everyday life through sweeping changes in technology, agriculture, and commercial exchange.

Transforming Technology and Production

Innovations in the early nineteenth century dramatically increased productive capacity and supported the emergence of a more interconnected national economy. These advances not only boosted output but also altered how Americans conceived of work and economic opportunity.

Key Technological Breakthroughs

New machines allowed production processes to shift away from home-based or small-scale workshop systems toward more centralized, specialized, and efficient operations.

Textile machinery enabled faster spinning and weaving, encouraging the rise of the factory system in New England.

Steam engines powered mills and transportation, reducing reliance on water-power sites and expanding industrial locations.

Interchangeable parts, introduced most prominently in firearms manufacturing, standardized production and reduced costs by allowing components to be mass-produced.

The telegraph sped communication, knitting distant markets together and enabling faster commercial decision-making.

Interchangeable Parts: A manufacturing system in which standardized components can be substituted for each other, enabling mass production and simplified repair....

These developments encouraged Americans to think of economic growth as limitless and increasingly dependent on innovation rather than traditional forms of labor.

Factory Growth and New Work Patterns

The shift toward factory production altered American labor. Wage work expanded, especially in textile centers such as Lowell, where young women entered the labor force in unprecedented numbers.

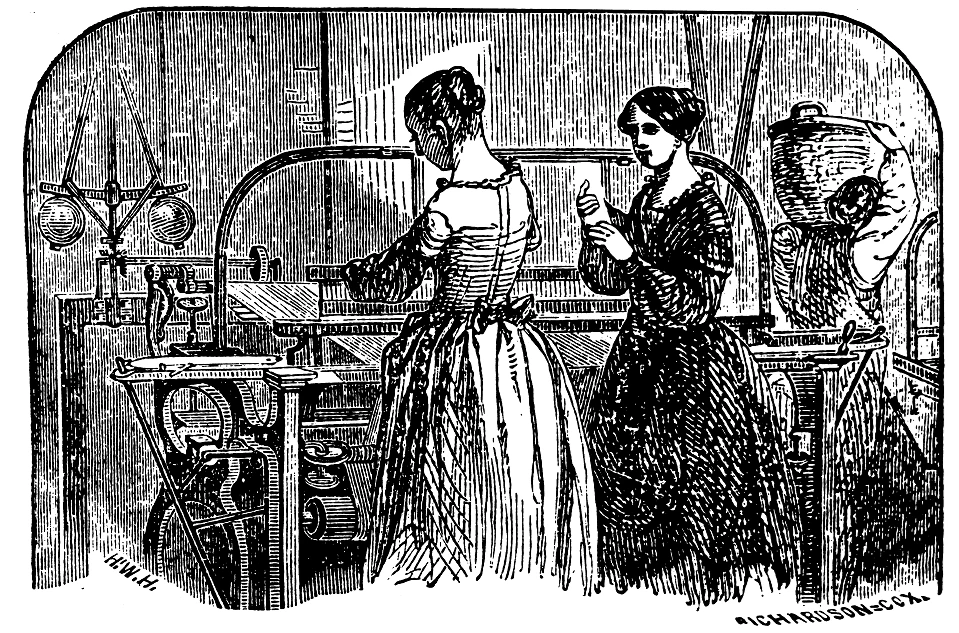

This nineteenth-century illustration shows young women operating power looms in a large textile mill, representing the Lowell mill girls who became a key industrial labor force. It highlights the scale of factory machinery, the crowded work environment, and the shift from household production to regimented wage labor. The image comes from a later publication and includes some details beyond the AP syllabus, but it accurately captures the essential features of early factory work and gender roles in the period. Source.

Workers adapted to timed labor, regimented tasks, and employer discipline, replacing the older rhythms of household production. Industrialization also heightened class distinctions by creating clearer divisions between owners, managers, and laborers.

Expanding Agriculture and Commercial Farming

Technological and market changes also transformed agriculture, allowing farmers to increase yields and participate more fully in commercial exchange.

Rising Productivity in Northern Farms

Farmers in the North and Midwest adopted inventions that improved efficiency and reduced labor demands.

Steel plows helped break tough prairie soil.

Mechanical reapers sped the harvesting of wheat and other grains.

Improved breeding, fertilizers, and crop rotations supported more reliable yields.

These innovations made it possible for northern farmers to shift from subsistence practices to commercial agriculture, producing surplus crops for distant markets. This shift illustrates how intertwined agricultural and industrial sectors became during the market revolution.

Commercial Agriculture: Farming oriented toward producing surplus goods for sale rather than solely for family subsistence.

Improved agricultural output sustained industrial workers and contributed to population growth in cities, strengthening regional economic interdependence.

Cotton and the Southern Economy

Although this subsubtopic focuses on background context, the broader market revolution included Southern cotton production, which became deeply tied to national and international commerce. Cotton’s rise depended on new technologies and soaring global demand, anchoring the South in plantation agriculture even as the North industrialized.

Expanding Transportation and Market Integration

Transportation innovations connected previously isolated communities and enabled goods, people, and ideas to move more quickly than ever before.

New Networks of Movement

Key developments during this period included:

Turnpikes, which improved overland travel and reduced transport time.

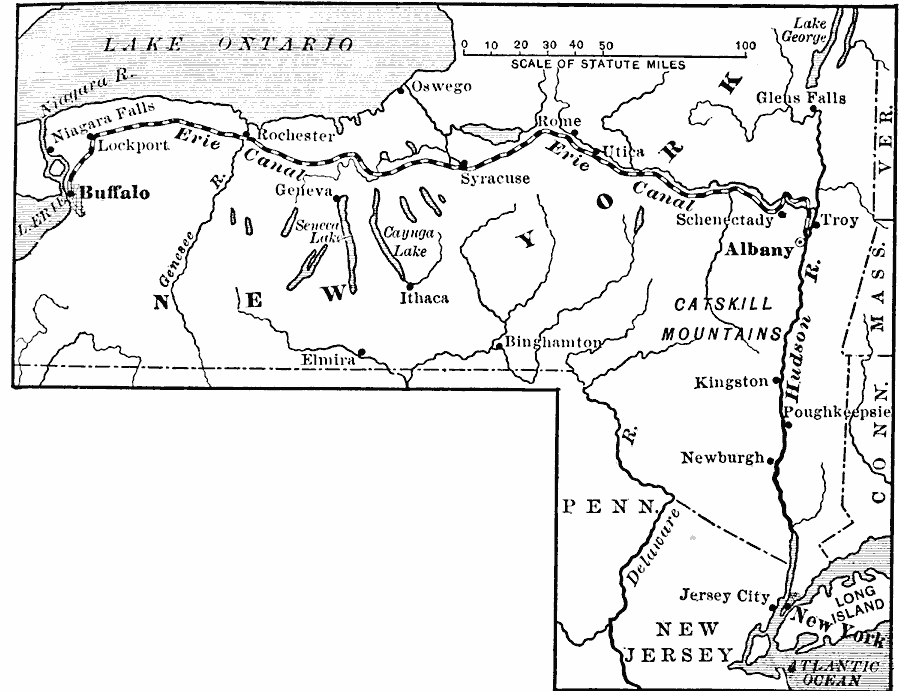

Canals, especially the Erie Canal, which dramatically lowered shipping costs and linked western farmers to eastern markets.

This historical map traces the route of the Erie Canal across New York State, linking Lake Erie with the Hudson River and New York City. It illustrates how a single man-made waterway connected western farming regions to Atlantic ports, lowering shipping costs and encouraging commercial agriculture. The map includes town names and geographic details that go beyond the syllabus but help situate the canal within the broader regional landscape. Source.

Steamboats, which moved cargo and passengers upstream and along major river systems.

Railroads, which expanded in the 1830s and 1840s, offering faster all-weather transportation.

These networks facilitated large-scale exchange across regions.

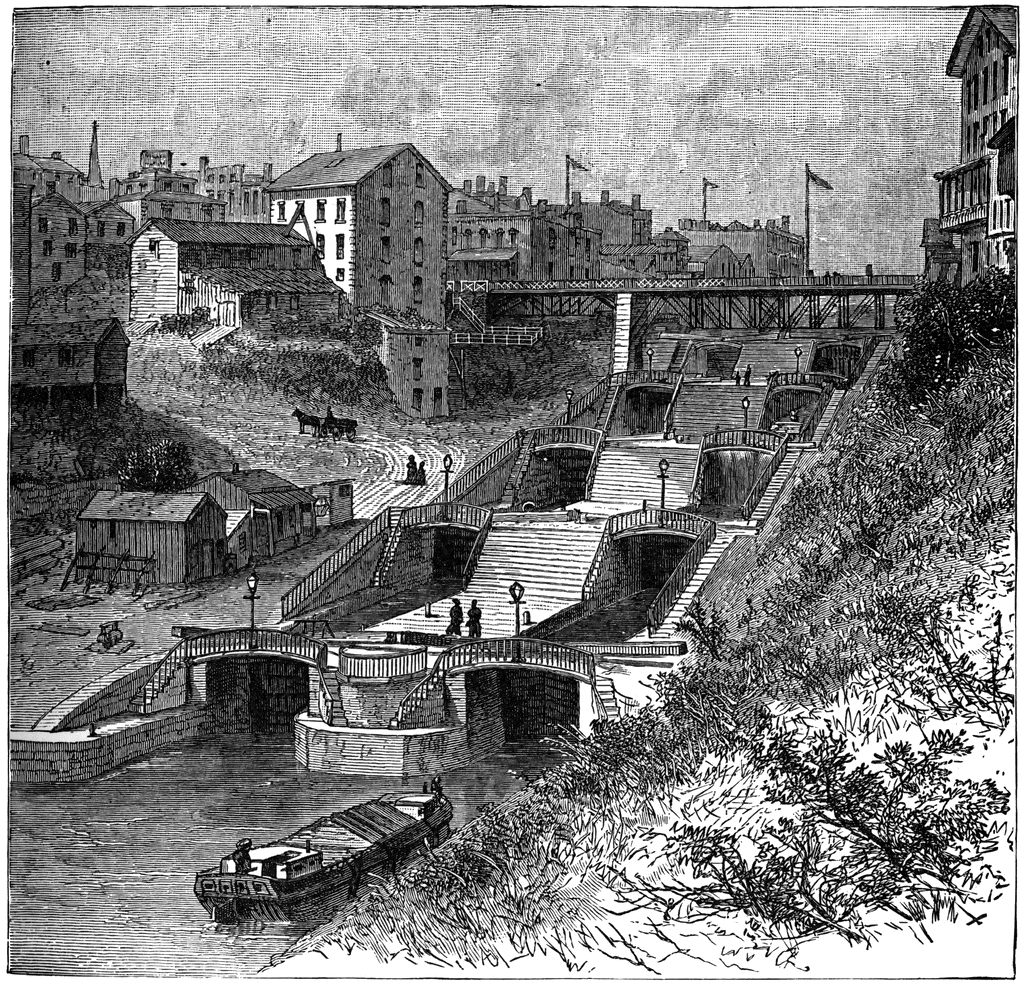

This engraved view of locks on the Erie Canal shows boats moving through a stepped lock system, with urban buildings and workers surrounding the waterway. It visually demonstrates how canal engineering overcame changes in elevation, allowing continuous traffic between interior farm regions and coastal markets. The scene includes additional urban detail and people not mentioned in the syllabus, but these elements help convey the canal’s role in reshaping towns and everyday work. Source.

As goods moved more freely, the United States shifted from a collection of relatively isolated local economies to a more unified commercial system.

Government Support and Legal Changes

State legislatures and courts promoted transportation growth by granting charters, providing subsidies, and supporting corporate expansion. This reflected a growing belief that infrastructure investment served the public good by encouraging commerce and settlement. Legal decisions that protected contracts and corporate rights further strengthened the market economy and established a regulatory environment favorable to business expansion.

Social Change and Regional Identities

Transformations in technology, agriculture, and commerce reshaped society and varied by region, influencing how Americans understood their place within the nation.

Urbanization and Labor Shifts

Cities expanded as factories and commercial hubs attracted workers. Urban growth fostered new social classes, including:

A rising middle class connected to managerial and professional roles.

A growing population of wage laborers, many of them recent immigrants.

Wealthy industrial and commercial elites who invested in expanding markets.

These demographic and class changes created distinct social environments compared to rural communities.

Regional Differences Strengthened

Improved transportation, rising agricultural productivity, and expanding industry deepened differences among the North, South, and West.

The North grew more industrial and urban.

The West developed commercial agriculture tied to northern markets.

The South remained centered on staple-crop agriculture and slavery.

These divergent regional paths formed the background context for political debates and emerging sectional tensions during the first half of the nineteenth century.

FAQ

Rural families increasingly shifted from producing goods solely for their own use to participating in expanding commercial markets. This meant growing more surplus crops, adopting new tools, and purchasing manufactured goods previously made at home.

Local stores became more common, offering products such as cloth, farm tools, and household goods. Rural communities also saw more circulation of cash, credit, and market prices, tying them indirectly to national economic trends.

Credit allowed farmers, merchants, and manufacturers to invest in land, tools, and equipment before they had cash on hand. These loans supported risk-taking and expansion.

Banks issuing banknotes increased the money supply, encouraging commercial transactions. However, uneven regulation meant that the value of notes could vary by region, contributing to occasional financial instability.

New transport routes made it easier and cheaper for families to move westward. Canals and roads opened access to fertile land in the Old Northwest.

Urban migration also rose. Workers seeking wages travelled towards factory towns and commercial centres, contributing to emerging labour markets and more diverse regional populations.

Many feared that wage labour undermined traditional independence and self-sufficiency. Factory discipline and reliance on employers challenged older ideals of artisanal control over work.

Others criticised the growing divide between rich and poor. Small farmers sometimes worried about debt, volatile prices, and the growing influence of banks, corporations, and distant markets.

The telegraph and faster printing presses allowed political news, party messages, and election information to circulate rapidly.

This encouraged:

• More organised national political parties

• Wider voter mobilisation

• Greater participation in debates on economic policy and reform

Even remote communities became more connected to national political developments, strengthening the sense of a shared political culture.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Identify and briefly explain one way in which technological innovation contributed to economic change during the Market Revolution (1800–1848).

Question 1

• 1 mark for identifying a relevant technological innovation (e.g., interchangeable parts, the telegraph, steam engines, textile machinery).

• 1 mark for accurately describing what the innovation was or how it functioned.

• 1 mark for explaining how it contributed to economic change (e.g., increased production efficiency, encouraged factory growth, expanded markets, enabled mass production).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Explain how developments in transportation reshaped regional identities in the United States during the Market Revolution. In your answer, refer to specific examples of transportation improvements and their economic and social effects.

Question 2

• 1 mark for identifying at least one major transportation development (e.g., canals, steamboats, railways, turnpikes).

• 1 mark for explaining how this innovation promoted greater market integration.

• 1 mark for describing its effect on a specific region (e.g., linking western farmers to eastern cities, growth of northern industry).

• 1 mark for explaining how these effects contributed to the formation or strengthening of distinct regional identities.

• Up to 2 additional marks for detailed examples or well-developed analysis, such as the role of the Erie Canal in connecting the Midwest to the Northeast or the way railways accelerated regional specialisation.