AP Syllabus focus:

‘The transition to broader participation expanded suffrage from property requirements to voting by all adult White men and coincided with the growth of political parties.’

Between 1800 and 1848, expanding suffrage reshaped American political life as increasing numbers of White men gained voting rights, fueling mass participation and the rapid rise of organized parties.

Expanding Suffrage in the Early Republic

The early nineteenth century marked a major shift in American democratic participation as many states broadened voting rights. Initially, most states required property ownership to vote, based on the belief that those with economic independence possessed the judgment necessary for political decision-making. These assumptions began to erode as Americans embraced more egalitarian ideals.

This 1815 painting depicts an Election Day crowd composed largely of White men, illustrating the early nineteenth-century expansion of political participation while highlighting who remained excluded from voting. Source.

The Decline of Property Requirements

Beginning in the early 1800s, state constitutional conventions revisited suffrage rules.

By the 1820s and 1830s, most states eliminated property qualifications, replacing them with requirements based on taxpaying or White manhood suffrage.

Frontier states such as Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois led the way, encouraging older states to follow to avoid losing population and political influence.

As political leaders sought broader legitimacy, the belief grew that political participation should reflect the will of ordinary White men, not just economic elites.

White Manhood Suffrage: The expansion of voting rights to all adult White men regardless of property ownership.

The shift toward universal White manhood suffrage elevated the political importance of individuals without substantial landholdings, who became a newly empowered voting bloc.

Persistence of Exclusion

Despite expanded opportunities for many White men, access to political participation remained sharply limited for other groups.

Women, regardless of race, were excluded from voting everywhere.

Free Black men faced increasing restrictions, with many northern states revoking earlier voting rights.

American Indians and enslaved people were categorically excluded from citizenship and suffrage.

These limits reveal the contradictory nature of early nineteenth-century democracy: expanding freedom for some while entrenching inequality for others.

The Growth of Political Parties

As the electorate expanded, American political culture transformed from elite-driven politics to mass-based party competition. With more voters participating, political organizations developed new strategies to appeal to a broader public.

The Decline of the First Party System

In the early 1800s, the Federalist Party weakened significantly due to its opposition to the War of 1812 and its alignment with elite interests.

The Democratic-Republicans emerged as the nation’s dominant party, but internal factionalism soon created divisions.

During the Era of Good Feelings, competition appeared to diminish, but beneath the surface, regional and ideological splits intensified.

As new voters entered politics, many demanded clearer policy distinctions, meaningful party choices, and leaders who reflected their interests.

The Rise of the Second Party System

By the 1820s and 1830s, emerging divisions led to the formation of two major political parties:

The Democratic Party, led by Andrew Jackson, emphasizing limited federal government, states’ rights, and support for the “common man.”

The Whig Party, influenced by Henry Clay’s views, favoring federal involvement in economic development and internal improvements.

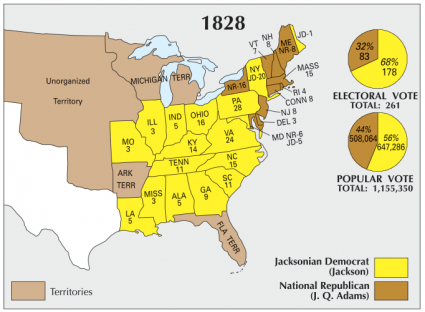

This map shows the state-by-state results of the 1828 presidential election, illustrating how mass party competition became national in scope. Extra details such as electoral-vote totals appear but help contextualize the growing influence of organized parties. Source.

These parties developed sophisticated organizational systems:

Local and state party committees

National nominating conventions to select presidential candidates

Coordinated campaign messaging

Party newspapers that shaped public opinion

Party activity became increasingly visible in everyday life through rallies, parades, and public meetings, reflecting the new mass-democratic culture.

Changing Political Practices and Popular Participation

The shift from property-based voting to broader suffrage fundamentally altered political practices. As political power dispersed among more voters, parties adapted their methods to mobilize supporters.

Campaign Innovations and Voter Engagement

With more Americans eligible to vote, political leaders sought to build emotional and cultural identification with their parties.

Politicians traveled widely, delivering speeches and building personal connections.

Campaign materials, like banners and badges, encouraged partisan enthusiasm.

Public events, including barbecues and marches, fostered community participation.

These developments contributed to some of the highest voter turnout rates in American history.

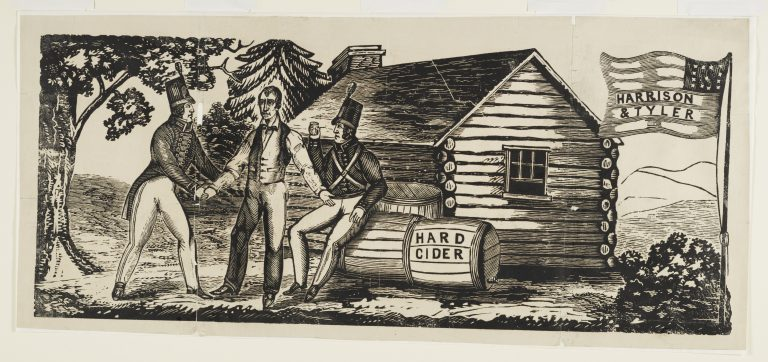

This 1840 campaign woodcut uses log cabin and hard-cider symbolism to appeal to ordinary voters, illustrating how parties mobilized the expanding electorate. Although it includes extra scene details, they reinforce the era’s emphasis on popular engagement and political imagery. Source.

Political Mobilization: The process of encouraging and organizing voters to participate in elections and support specific parties or candidates.

Party loyalty became a defining feature of civic identity, and political affiliation often shaped views on economic policy, federal power, and social issues.

Broadening Political Identity

As voting rights expanded for White men, many began to see themselves as active participants in shaping national direction.

The idea of the “self-made man” gained prominence, linking political independence to economic opportunity.

Widespread belief in popular sovereignty reinforced the conviction that government should respond to the will of ordinary citizens.

American society increasingly connected civic participation with masculinity and independence, excluding those who did not meet these cultural and legal standards.

Sectional Dimensions of Expanding Suffrage

Although suffrage broadened nationally, regional variations influenced political culture.

Northern states often paired expanded suffrage with rising expectations for civic education and participation.

Southern states, while adopting White manhood suffrage, intensified restrictions on free Black residents as slavery expanded.

Western states promoted broad suffrage to attract settlers and strengthen claims to self-government.

These differences shaped regional political identities and contributed to emerging sectional tensions.

The Link Between Suffrage Expansion and Party Competition

The broadening of the electorate and the rise of mass parties reinforced one another. As more citizens gained access to political participation, organized parties became essential to mobilizing and representing voters. In turn, the growth of parties encouraged states to continue democratizing their suffrage laws. The early nineteenth century thus witnessed a dynamic interplay between expanding political rights and the development of a more vibrant, competitive party system.

FAQ

Advances in printing technology, especially cheaper newspapers and mass-produced pamphlets, enabled parties to communicate directly with a wider electorate.

Partisan newspapers became central tools for shaping public opinion, offering editorials, speeches, and political cartoons that reinforced party identity.

These papers also standardised party messaging across regions, helping local branches coordinate with national leaders.

Frontier states sought to attract settlers and promote rapid population growth, both for economic development and political leverage in Congress.

With sparse populations and younger social hierarchies, frontier communities were less tied to traditional property-based political structures.

Offering broad voting rights helped project an image of opportunity and equality, giving these states a competitive edge over older states in the East.

Parties organised parades, barbecues, and public festivals that blended entertainment with political messaging.

These events fostered community identity and made political participation feel like a shared cultural practice rather than an elite process.

• Public toasts, songs, and symbolic imagery (such as log cabins) strengthened emotional connections to candidates and reinforced party loyalty.

Local committees were responsible for maintaining regular contact with voters through neighbourhood canvassing, distributing printed materials, and organising meetings.

They acted as intermediaries between national party leaders and local communities, ensuring that national messages were adapted to local concerns.

By coordinating election-day logistics, such as transportation to polling places, they expanded participation and helped normalise party involvement in everyday life.

As more White men gained the vote, leaders were increasingly expected to demonstrate personal accessibility, military service, or humble origins that resonated with ordinary voters.

Politicians adapted by emphasising relatable qualities and downplaying elite backgrounds.

• Candidates travelled more widely

• Delivered speeches aimed at broad audiences

• Adopted imagery portraying themselves as defenders of the “common man”

This shift helped redefine leadership as grounded in popular appeal rather than social rank.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which the expansion of suffrage in the early nineteenth century contributed to the growth of political parties in the United States.

Question 1

Award up to 3 marks:

1 mark for identifying a valid connection (e.g., broader suffrage increased voter participation).

1 mark for explaining how increased participation required more organised political mobilisation (e.g., parties developed new campaign methods to reach mass electorates).

1 mark for linking the change to the emergence or strengthening of national parties such as the Democrats and Whigs.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Analyse the extent to which the expansion of White manhood suffrage between 1800 and 1848 transformed American political culture.

Question 2

Award up to 6 marks:

1 mark for a clear statement addressing the extent of transformation (e.g., significant, limited, or mixed).

1 mark for describing the removal of property requirements and the broadening of the electorate.

1 mark for explaining effects on party organisation (e.g., rise of mass parties, nominating conventions, campaign innovations).

1 mark for discussing increased political participation, including higher voter turnout and popular campaigning.

1 mark for addressing the limits of change (e.g., continued exclusion of women, free African Americans, American Indians, and enslaved people).

1 mark for providing a historically accurate example or detail that supports the argument (e.g., Jacksonian Democracy, 1828 election mobilisation).