AP Syllabus focus:

‘From 1800 to 1848, the United States developed a more modern democracy and debated how to align society and institutions with democratic ideals.’

A dynamic period of political transformation between 1800 and 1848 witnessed the United States experimenting with broader participation, shifting political authority, and redefining democratic values as the young republic matured.

The Evolution of Democratic Ideals in the Early Republic

During this era, Americans increasingly linked political legitimacy to the participation of ordinary citizens. Leaders and reformers debated how far democratic principles should extend and how they should reshape institutions. These conversations unfolded alongside demographic growth, territorial expansion, and social change brought about by the early market economy.

Jeffersonian Visions of Democracy

Thomas Jefferson’s presidency in 1801 represented an early turning point toward a more egalitarian political ethos among White male citizens. His belief in a “republic of yeoman farmers” emphasized virtue, independence, and limited government as foundations for preserving liberty.

Republicanism: A political philosophy holding that governments derive authority from the people and must promote civic virtue and the common good.

Jeffersonian policies—such as reducing the national debt, scaling back the military, and opposing Federalist economic programs—reflected distrust of concentrated federal authority. Although these policies did not dismantle centralized power, they encouraged a broader expectation that leaders should respond to the public rather than elite interests.

Broadening Access to Political Participation

Between 1800 and 1848, many states moved gradually away from property-based voting requirements, opening political participation to a larger segment of White men. This shift strengthened the idea that political rights should rest on citizenship rather than wealth.

States rewrote constitutions to eliminate property qualifications.

George Caleb Bingham’s “The County Election” (1854) depicts a crowded local election day with White male voters talking, lining up to cast ballots, and engaging in partisan persuasion. The scene captures the energy and informality of early nineteenth-century mass politics. The painting highlights the racial and gender limitations of democratic participation during the era. Source.

Western states entered the Union with more democratic voting rules.

Political leaders increasingly appealed to ordinary White male voters.

Rising political competition encouraged parties to adopt more inclusive rhetoric.

This expanding electorate did not reflect universal democratic rights. Women, African Americans (even those free in the North), Native Americans, and many immigrants remained excluded, illustrating the gap between democratic ideals and their implementation.

Debating Democratic Governance and Institutional Power

As democratic participation widened, Americans questioned how institutions should adapt. Conflicts emerged over the balance of power among branches of government, federal versus state authority, and the appropriate scope of public influence.

The Supreme Court under Chief Justice John Marshall reinforced federal supremacy and judicial review, often clashing with states’ rights advocates who claimed that democratic governance required local control. Meanwhile, the executive branch evolved as presidents from Jefferson to Jackson asserted stronger leadership roles, prompting debates over whether expanded executive power aligned with or threatened democratic ideals.

The Rise of Mass Politics

Expanding democracy reshaped political culture. By the 1820s and 1830s, the United States entered an age of mass politics, characterized by highly organized parties, public rallies, and vigorous voter engagement.

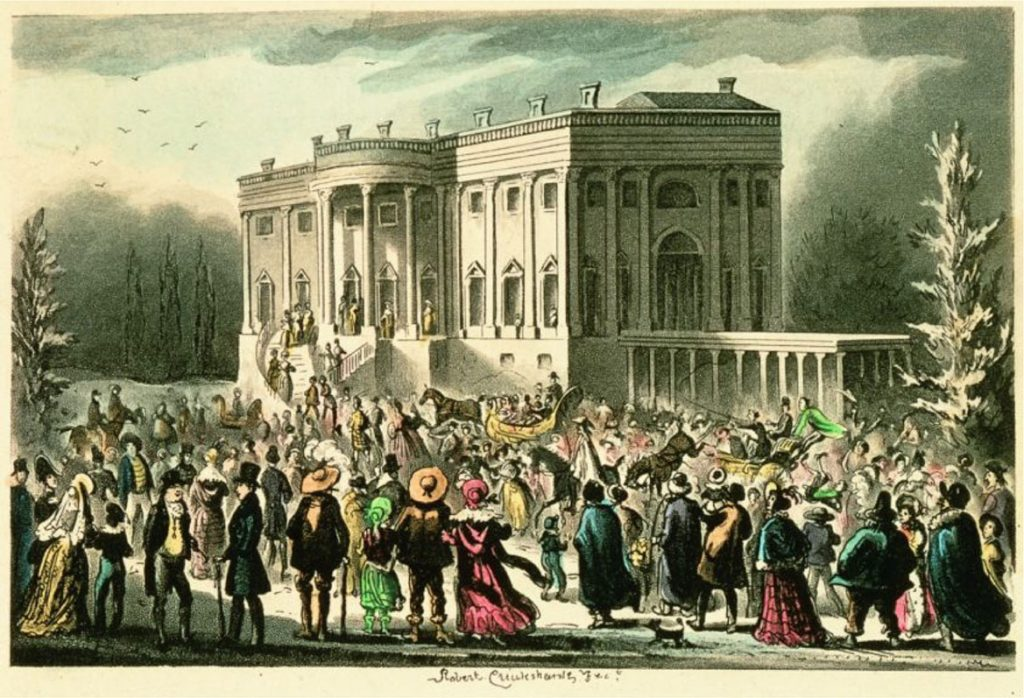

This 1841 engraving shows throngs of ordinary people rushing toward the White House to celebrate Andrew Jackson’s 1829 inauguration, illustrating the rise of mass democratic participation. The image captures the turbulent, highly public nature of Jacksonian political culture. It reflects contemporary perceptions of popular democracy even though it was created slightly later. Source.

Newspapers multiplied and aligned with parties, shaping public opinion.

Campaigning shifted from elite negotiation to public persuasion.

The Second Party System, featuring Democrats and Whigs, mobilized voters on a national scale.

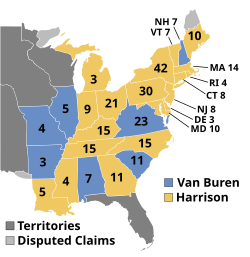

This electoral map of the 1840 presidential contest illustrates the national reach of Whig and Democratic party competition during the Second Party System. It demonstrates how organized parties mobilized voters across multiple states. The inclusion of state vote totals adds detail beyond the syllabus but helps contextualize mass political participation. Source.

Second Party System: The structured two-party competition between Democrats and Whigs beginning in the 1820s, marked by mass mobilization and national political organization.

These changes created a political environment in which ordinary voters played a critical role in shaping policy debates, even as many groups still lacked access to political rights.

Democratic Ideals and Social Reform Impulses

Growing belief in the value of individual equality and moral improvement intersected with religious revivalism, inspiring Americans to challenge existing social structures. Reformers linked democratic ideals to movements for temperance, public education, abolitionism, and women’s rights. Although reform efforts varied widely in goals and methods, they reflected a shared conviction that citizens should actively shape society.

This reform impulse intensified tensions among regions as Northern and Southern communities developed increasingly distinct assumptions about democracy, morality, and the legitimacy of slavery. These divisions underscored the difficulty of reconciling the nation’s democratic rhetoric with entrenched social and racial hierarchies.

Territorial Expansion and Democratic Identity

The belief in an expanding democracy also underpinned the era’s territorial ambitions. Leaders claimed that spreading American institutions across the continent would strengthen liberty and opportunity for White settlers. Yet territorial expansion heightened debates about citizenship, governance, and the extension of slavery. These issues forced Americans to confront the contradictions within their democratic ideals and question who should enjoy full rights.

The Meaning of Modern Democracy, 1800–1848

By 1848, the United States had developed a more participatory political system for White men, expanded expectations of public involvement, and articulated a powerful set of democratic ideals. However, persistent exclusion, institutional conflict, and sectional divisions revealed the incomplete and contested nature of democracy in this era. The period established foundational debates—about equality, rights, and the role of government—that continued to shape American political development.

FAQ

The rapid spread of newspapers made political information available to more ordinary Americans, allowing voters to make choices based on party platforms and current events.

Print culture also encouraged competitive parties to communicate directly with a broad electorate, helping to normalise political persuasion and public mobilisation.

Cheaper printing and wider literacy meant political messages reached frontier communities, strengthening participatory expectations across regions.

Artisans, small farmers, and frontier settlers tended to support expanded suffrage because it increased their political influence and reduced elite dominance in policymaking.

Western states especially championed universal White manhood suffrage because broad participation helped attract settlers and promote the region’s democratic identity.

Urban labourers often supported these changes as well, seeing them as a defence against entrenched political and economic hierarchies.

Politicians increasingly framed themselves as champions of the “common man,” appealing to voters through informal language, public events, and populist messaging.

Campaign strategies emphasised shared identity and everyday concerns, portraying elite candidates as out of touch with ordinary citizens.

These rhetorical shifts reinforced the belief that political legitimacy depended on responsiveness to the majority of White male voters.

As more White men voted, presidents were expected to demonstrate a closer connection to the public, often by travelling, giving public statements, or emphasising personal humility.

Presidential campaigns became national events, with candidates projected as symbols of popular will rather than elite statesmen.

The rise of mass parties meant presidents increasingly relied on organised political networks, shaping expectations of executive responsibility and accountability.

Regions adopted different interpretations of democratic ideals, contributing to political strain.

Northern states tended to emphasise reform, public education, and civic equality for White men.

Southern states prioritised local control and defended hierarchies tied to slavery.

Western communities embraced broad suffrage but also supported strong assertions of settler rights over Indigenous populations.

These contrasting regional priorities challenged national unity even as democratic participation expanded.

Practice Questions

Question 1(1–3 marks)

Identify one way in which political participation expanded for White men in the United States between 1800 and 1848.

Question 1

Award up to 3 marks:

1 mark for identifying a valid expansion of political participation (e.g., removal of property requirements for voting).

1 additional mark for providing brief context or elaboration (e.g., Western states adopting universal White manhood suffrage).

1 additional mark for accurately linking the change to broader democratic trends (e.g., parties appealing to broader electorates).

Maximum: 3 marks

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Explain how debates over democratic ideals influenced political developments in the United States between 1800 and 1848. Use specific historical evidence to support your answer.

Question 2

Award marks according to the following criteria:

1 mark for a clear statement explaining how democratic ideals shaped political developments (e.g., belief in popular sovereignty encouraging mass politics).

1–2 marks for specific evidence supporting the explanation (e.g., rise of the Second Party System; Jacksonian appeal to ordinary White voters; constitutional reforms expanding suffrage).

1–2 marks for linking debates over democracy to changes in institutions or political culture (e.g., disputes over federal vs. state power; executive authority; growth of party conventions).

1 mark for demonstrating understanding of limitations or contradictions of democratic ideals (e.g., racial and gender exclusions).

Maximum: 6 marks