AP Syllabus focus:

‘Political boundaries often coincide with cultural, national, or economic divisions; however, some boundaries are created by demilitarized zones or policy decisions.’

Political boundaries shape how societies interact by marking where authority begins and ends. These borders often reflect cultural, national, or economic divisions, influencing identity, cooperation, and conflict.

Political Boundaries and Human Geography

Political boundaries are central to understanding how space is organized by states and other governing bodies. While some borders reflect long-standing cultural or national divisions, others are created through policy decisions or imposed conditions. These different origins affect how people interact, move, trade, and identify within their environments.

Political Boundary: A legally defined line that marks the limits of a state’s or governing body’s jurisdiction and authority.

A political boundary may coincide with existing cultural divisions or, alternatively, disrupt communities and economic networks. Understanding how these borders emerge and operate is essential for analyzing geopolitical relationships and the lived experiences of people within different regions.

Cultural Divisions and Boundaries

Cultural divisions include differences in language, religion, tradition, and ethnicity. Boundaries aligned with cultural patterns often emerge organically or through political negotiations that attempt to minimize cultural conflict.

How Cultural Divisions Shape Borders

Ethnolinguistic differences may encourage states to draw boundaries that group similar cultural populations together.

Religious contrasts can reinforce border placement, especially where competing religious communities prefer political autonomy.

Historical territorial claims rooted in cultural heritage may influence where a boundary is accepted or contested.

Cultural cohesion within borders can strengthen national identity and political stability.

When political boundaries correspond to cultural divisions, states may experience reduced internal conflict. However, they can also solidify distinctions between groups, limiting cross-cultural interaction and increasing ethnic nationalism.

Impacts When Boundaries Cut Across Cultures

Boundaries that divide culturally similar populations can lead to long-term tension. This often occurs where borders were drawn during colonial rule or conflict negotiations without regard for local cultural landscapes.

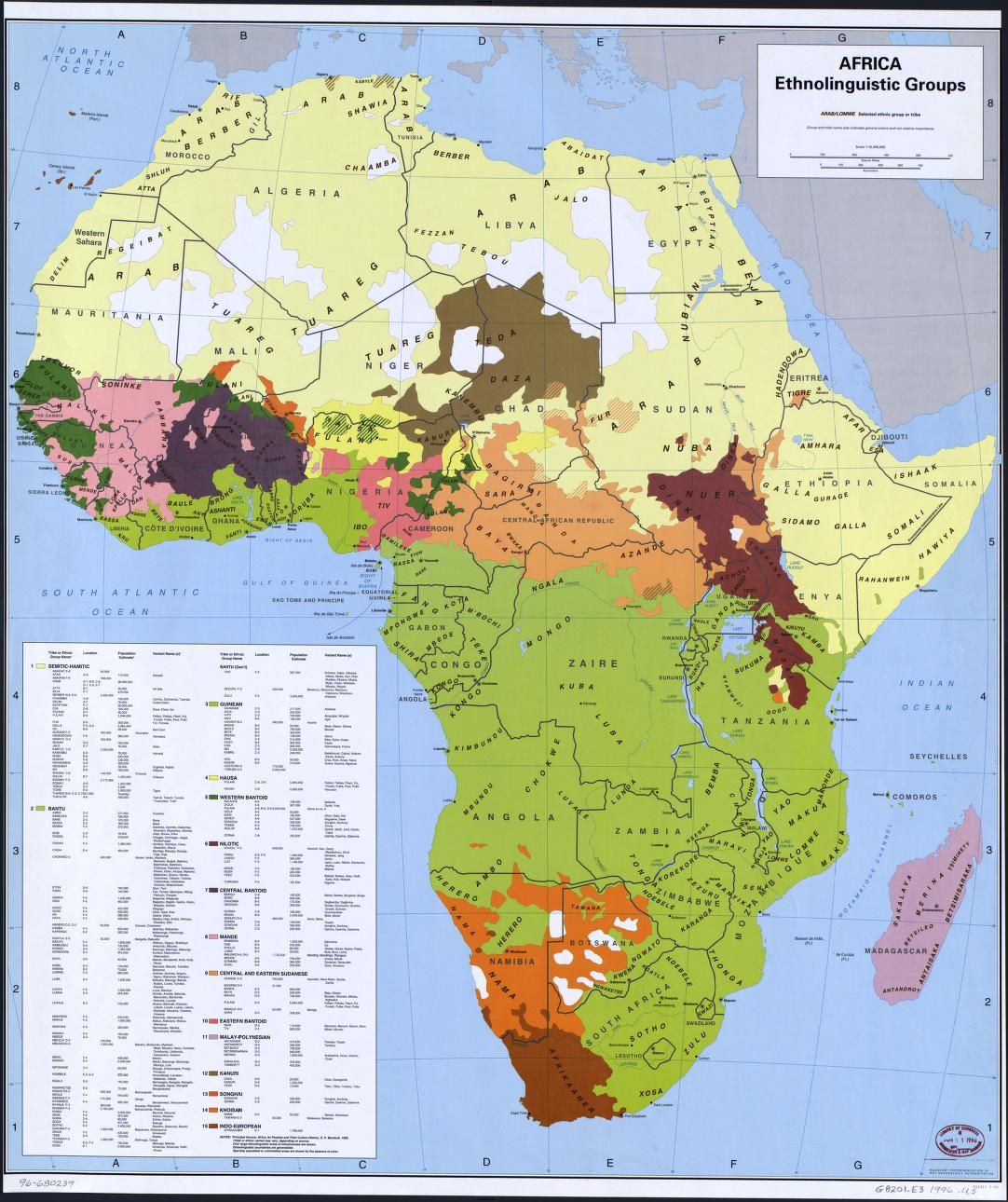

Africa, ethnolinguistic groups. This map shows major ethnolinguistic regions color-coded across the continent, with thin black lines marking contemporary state boundaries. The detailed legend includes more categories than required by the AP syllabus, so it should be used primarily to visualize how cultural regions and political borders often fail to align. Source.

Consequences may include:

Fragmentation of ethnic or linguistic groups

Competing territorial claims

Reduced cultural autonomy

Increased potential for separatist movements

National Divisions and Boundary Formation

National identity, defined by shared political allegiance, culture, and history, also influences boundary creation. A nation is a group of people with a shared cultural identity who desire self-rule, while a state is a political unit with sovereign control.

Boundaries That Reflect National Identity

States may draw borders to unite people who identify as one nation, supporting political legitimacy.

National divisions may produce strong centripetal forces that encourage unity within a boundary.

When national groups span multiple states, borders may be disputed or renegotiated.

Many independence movements arise because nations seek political boundaries that match their perceived national homeland. This can reshape regional political landscapes and stimulate new border creation.

Economic Divisions and Boundary Effects

Economic differences, such as disparities in wealth, industry, or resource distribution, frequently influence political boundary placement and interaction.

How Economic Factors Shape Boundaries

Resource-rich areas may become contested border regions.

Trade corridors can determine where states negotiate or reinforce boundaries.

Economic inequality across a boundary may affect migration, smuggling, and labor patterns.

Industrial and agricultural zones can become internal or external divisions that policymakers consider during boundary-making.

Economic boundaries may be intentionally established to protect markets, restrict movement, or manage taxation. These borders can also reflect historical inequalities encoded into political geography.

Demilitarized Zones and Policy-Created Boundaries

Not all boundaries reflect cultural, national, or economic divides. Some are created deliberately through agreements or security arrangements.

Demilitarized Zones (DMZs)

A demilitarized zone is an area where military forces and installations are prohibited. DMZs are often established after conflict to reduce the risk of renewed violence.

Key characteristics:

They act as buffer zones between hostile or formerly hostile states.

They may restrict civilian movement and economic activity.

They can unintentionally form ecological preserves due to limited human activity.

Policy-Driven Boundaries

Some boundaries emerge from administrative decisions rather than social geography. Governments may create or adjust borders for:

Electoral districting

Regional governance reforms

Environmental protection zones

Migration control and border security

These policy-created borders may cut across cultural or economic landscapes but serve broader administrative or political goals.

Interactions at Cultural, National, and Economic Boundaries

Political boundaries influence how communities interact socially, politically, and economically.

Key Patterns of Interaction

Cross-border trade may flourish or decline depending on how permeable boundaries are.

Cultural exchange can occur where boundaries are open or become restricted where borders are tightly controlled.

Identity formation may be reinforced at borderlands where cultural groups meet or divide.

Conflict or cooperation may emerge depending on how borders align with local populations and economic systems.

Boundaries are dynamic, reflecting ongoing changes in politics, culture, economics, and policy decisions. Understanding their relationship with human divisions provides insight into local, regional, and global political processes.

“The Koreas at Night,” an astronaut photograph from the International Space Station, shows brightly lit South Korea and a largely dark North Korea separated by the land border. This visual illustrates stark differences in economic activity, energy use, and infrastructure across a political boundary. Surrounding regions show additional urban illumination not required by the AP syllabus but help contextualize the contrast. Source.

FAQ

Historical migration often creates culturally mixed regions that later become sites of political border negotiations. When groups settle across wide areas, subsequent borders may split related communities.

Over time, these historic patterns can produce:

• regions with layered identities

• borderlands where multiple cultures converge

• political pressure to recognise cultural autonomy

This helps explain why some boundaries remain contested long after they are drawn.

Cultural boundaries stay informal when the groups involved do not seek statehood, when there is strong political integration, or when governments prioritise unity over cultural separation.

They become formal borders when:

• cultural groups push for autonomy or independence

• governments seek to stabilise tensions by recognising divisions

• international actors intervene to formalise settlements

The shift often reflects political, not purely cultural, motivations.

Shared culture can foster cooperation by enabling easier communication, mutual trust, and cross-border economic activity. These regions often develop as integrated cultural corridors rather than divided territories.

Cooperation may include:

• shared festivals, media, or heritage projects

• joint economic initiatives

• cross-border governance arrangements for transport or resources

Such regions highlight how boundaries need not always inhibit cultural exchange.

Governments may adopt strategies to reduce tension and facilitate interaction across borders. These measures aim to avoid fuelling separatism or resentment.

Common approaches include:

• creating cross-border travel agreements

• allowing dual citizenship

• supporting cultural exchange programmes

• establishing regional councils to coordinate policy

These mechanisms help maintain stability while acknowledging cultural unity.

Economic inequalities often shape how communities near borders perceive themselves in relation to neighbouring states. Residents may develop hybrid or shifting identities based on economic opportunity rather than cultural affiliation.

Border communities might:

• associate more closely with the economically stronger state

• experience tensions between traditional identity and economic incentives

• become hubs of informal trade that reshape local social structures

Economic contrasts can therefore play a powerful role in redefining identity at political boundaries.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which a political boundary may reflect a cultural division.

Mark scheme

Award up to 3 marks:

• 1 mark for identifying a cultural division, such as language, religion, or ethnicity.

• 1 mark for describing how a political boundary aligns with that division (for example, grouping culturally similar people within the same state).

• 1 mark for explaining why this alignment occurs, such as reducing cultural conflict or maintaining social cohesion.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using an example, analyse how economic differences across a political boundary can influence patterns of interaction between neighbouring states or regions.

Mark scheme

Award up to 6 marks:

• 1 mark for identifying a political boundary with significant economic differences.

• 1 mark for naming or describing a relevant example (for instance, the border between North and South Korea, or between Mexico and the United States).

• 1–2 marks for explaining how economic inequality affects cross-border interactions (such as migration, trade, labour flows, or smuggling).

• 1–2 marks for analysing the consequences of these interactions, which may include increased dependency, tension, or policy responses by one or both states.

• Maximum 6 marks for well-developed, accurate, and geographically informed analysis.